Four Questions You Must Answer to Build Your Positioning Strategy (by Anthony Pierri)

In this edition, Anthony Pierri breaks down the essential pillars of positioning for Product Marketers.

Imagine this:

You build a sparkling new SaaS product.

You have the financial muscle to promote it.

You even have a creative distribution strategy to get it to audiences.

However, those aspects alone won’t do much when your product category landscape looks like this circus:

The war for attention in SaaS is astronomical.

“Features” will no longer be a sustainable competitive advantage, especially as AI starts to catalyze engineering efforts. And all your competitors are also doing paid ads, social media “hot takes”, podcasts, and Tiktok trends.

On the flipside, target audiences are bombarded with new product pitches every day. My personal LinkedIn DMs are replete with cold approaches about the next “AI-powered game changer” product. The feed noise is deafening.

Before you can coax prospects with free trials and Sendoso gifts, they need to hear your pitch and decide whether they want to invest their time in you.

Now, let me be real: many products fail at this as they have AWFUL introductory messaging for their products.

Prospects hear a goulash of jargon, lofty benefits, and aspirational messages. They walk away without understanding the product or how it’s different from the 10 other identical options on the market.

Is there a way out?

Well, there’s one potent device that every Product Marketer needs to learn to create clarity and stand out: Positioning.

In the words of April Dunford:

"Positioning defines how your product is a leader at delivering something that a well-defined set of customers cares a lot about."

Many people think positioning is corporate jargon and fluff. I did, too.

Truth is that it’s THE key exercise every product marketing team sorely needs to do to begin to differentiate.

But just like learning a new language, people often don’t know where to start.

Until they stumble on Duolingo, of course.

So, I reached out to the “Duolingo of the positioning world” and asked if he would help us. And I got lucky.

We have none other than Anthony Pierri - a product marketing expert and co-founder of Fletch PMM - unpacking this murky subject today.

In recent times, he has been quite the LinkedIn enigma, racing to over 57,000 followers (as of this writing) in a short period of time. He regularly demystifies positioning & messaging with wisdom-rich posts and crystal-clear visual frameworks. If you haven’t already, give him a follow.

Anthony will break down the fundamental questions every Product Marketer needs to answer to start developing a positioning strategy.

Without further ado, here’s Anthony:

Four Questions You Must Answer to Build Your Positioning Strategy

Positioning is more complicated and less complicated than you think it is.

It's complicated because software is extremely amorphous. If you're in B2B SaaS, you're not selling shoes. You're selling a malleable tool that can look very different depending on who is behind the wheel.

You're trying to figure out an angle that will help tons of diverse buyers understand what you've built and why it matters... without sounding vague and buzz-wordy.

To make matters worse, your product itself is in a constant state of flux. You're launching new features at a breakneck speed, and while it might look like a shoe today... it could easily look like a car tomorrow... and a plane the following week.

It's complicated.

But on the simple side, you really just need to answer four questions:

1. What is it

2. Who is it for

3. What does it replace

4. Why is it better

I prefer to focus on the easier angle, so let's answer these questions together.

Questions 1 & 2: What Is It? (and by extension… Who is it for?)

Here is a statement that should be obvious (but isn’t):

If someone doesn’t know what you are talking about, they will immediately tune you out. They need a baseline understanding before any other meaningful interactions can occur.

Imagine you’re at a networking event. A potential customer asks you, “So, what’s your product?” How do you respond?

There are several bad ways to answer this question.

❌ Answer with an outcome

“It’s a way to make your team more efficient.”

While this may be true, it doesn’t actually answer their question. They’ll likely respond: “Cool! But what is it?”

❌ Answer with your mission statement

Unless you’re speaking with investors, any form of “we are democratizing (or disrupting) the ______ industry” will leave your conversation partner confused.

❌ Answer with a feature

Saying “it’s AI-powered” still begs the question… what is AI-powered?

Let’s move past the bad responses. There are two satisfactory answers to the “what is it” question:

1. State your product category

Once you name the product category you inhabit, you’ll have also explained what you’ve built.

”We’re an interaction design tool.”

“We’re an issue tracking tool.”

“We’re a marketing automation platform.”

If your conversation partner is in your target market, these answers propel the discussion forward. If you say, “We’re a CRM,” they might ask, “What makes you different from Salesforce?” This is exactly where you want the conversation to go. Now, you’re primed to speak about your differentiated value.

We call this Category-Based Positioning. You start with a defined group of products that already exists, then explain why your product is better.

Despite the straightforward clarity it brings, startups struggle with this approach. Often, they feel that if they’re doing something truly new, no category can accurately describe them.

“We are so much more than a CRM!”

While this may be true in some extreme cases, most new products are just variations of older products. Even OpenAI calls ChatGPT a “chatbot” — despite having the most powerful, innovative technology since the invention of the Internet.

While it might feel diminishing to your grander vision, choosing a category that is close to what your product is/does can be the difference between building a startup on easy mode… and building on hard mode.

Additionally, choosing a well-known category enables word-of-mouth. If customers can quickly explain what you do using a familiar category, they’re more likely to tell others.

Take Docusign. It’s far easier for customers to remember “eSignature software” (their actual category) than “Intelligent Agreement Management” (their invented category).

How do you ensure that your category is immediately recognizable? You’ll need to consider your audience.

In order to explain Figma to a product designer, you could call it an “interaction design tool.” However, the same category won’t mean anything to a CFO. They’d likely recognize a simpler phrase — “design tool.”

Because the audience is so critical, “global positioning” doesn’t exist. Instead, you’ll need to vary the level of abstraction depending on the knowledge of your audience.

Of course, you can’t be all things to all people… so many companies choose a leading positioning for their ideal customer profile. This messaging should appear in the “hero” section of the homepage (i.e. what goes above the fold) along with any public-facing marketing materials. You can also run concurrent campaigns to different audiences, but you’ll need to deploy tailored positioning strategies for each.

2. State your leading use case

Sometimes, no category will adequately cover what you do. This can happen for two reasons:

1. You’re doing something fundamentally different (i.e. quantum computing, blockchain, etc.).

2. Your product solves a hyper-specific pain point that’s too small to constitute its own category.

While most B2B founders believe they are in the first group, the vast majority fall into the second.

When Calendly launched, they couldn’t call themselves a “scheduling tool.” At the time, the term would evoke more confusion: “Scheduling tool? Scheduling for what?”

They also couldn’t call themselves “Calendar Software,” because they’d be compared to Google Calendar, Apple Calendar, etc. When lumped in this category, Calendly’s features are pretty weak… for starters, they don’t have a calendar at all!

In their case, it was much clearer to explain the product with the use case.

“It’s a tool for scheduling meetings over email.”

This strategy is called Use Case-Based Positioning.

(A quick definition: Use Case = a customer activity, workflow, or process that your product addresses)

Using this technique, you clearly state the exact scenario in which someone would use your product. In this way, you quickly answer the foundational question: “What is it?”

Those who employ a Use Case-Based strategy often hope that the use case will become so widespread that other vendors join the fray, and a dedicated product category will form.

If you monitor review sites like G2 and Capterra, you can see this phenomenon happening over and over. Startups will begin tackling a hyper-specific activity (i.e. “scheduling emails online”) and eventually the demand will grow, copycat tools will spawn, and a new category will emerge.

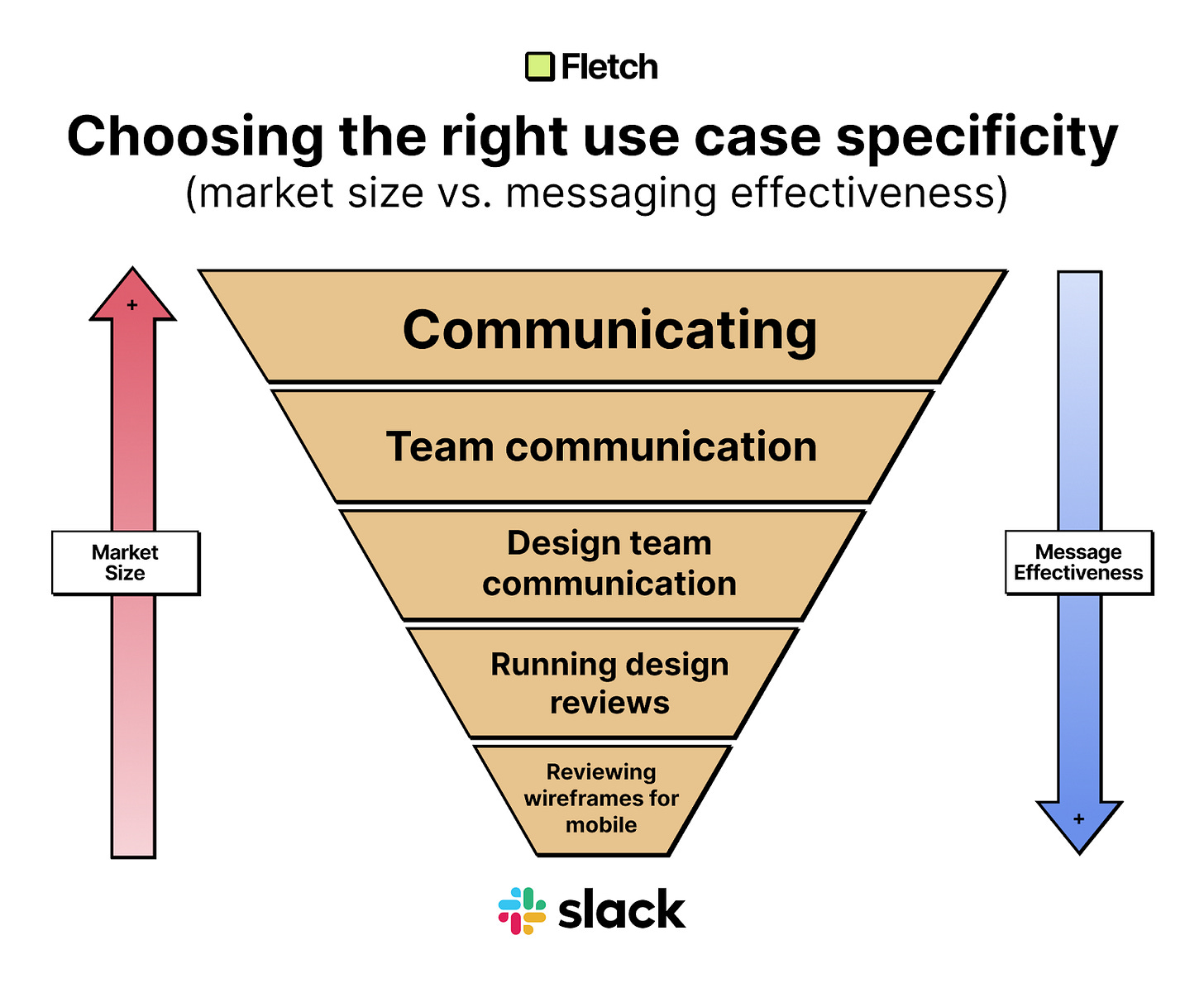

Just like categories, use cases are highly dependent on your customer. They fall on a spectrum of broad/abstract to narrow/concrete. At the highest level, Slack’s use case could be “communicating with people.” At a hyper-specific level, the use case could be: “reviewing wireframes for mobile.”

Choose the right level of specificity for your audience and the go-to-market asset they’ll be reading. Slack could use the design team use case on a targeted landing page, while they’d likely choose the broader option for their homepage.

When determining use case specificity, here is a rule of thumb:

- As you go more specific, your messaging effectiveness increases, but your target audience size decreases.

- As you go broader, your messaging effectiveness decreases, but your target audience size increases.

While sales conversations can be highly targeted to just one person, marketing needs to appeal to many people.

If you build a marketing message for “people named Jack who need to invite co-workers to a company birthday party,” you’ll definitely capture Jack’s attention… but he alone won’t sustain the business. You’ll likely need to go broader — messaging to “people who need to communicate with co-workers.”

Here’s the goal: find the sweet spot between the narrowness of the use case and the size of the market. That way, you can maximize the efficiency of your go-to-market motion and make meaningful progress towards your business goals.

Should you choose a Use Case or Category-based approach? You’ll need to answer “Who is it for?”

Your product may be amazing, but it’s highly unlikely that it’s helpful for all 8 billion people on the planet. Even if it was… your go-to-market muscle isn’t strong enough to carry your product to the ends of the earth.

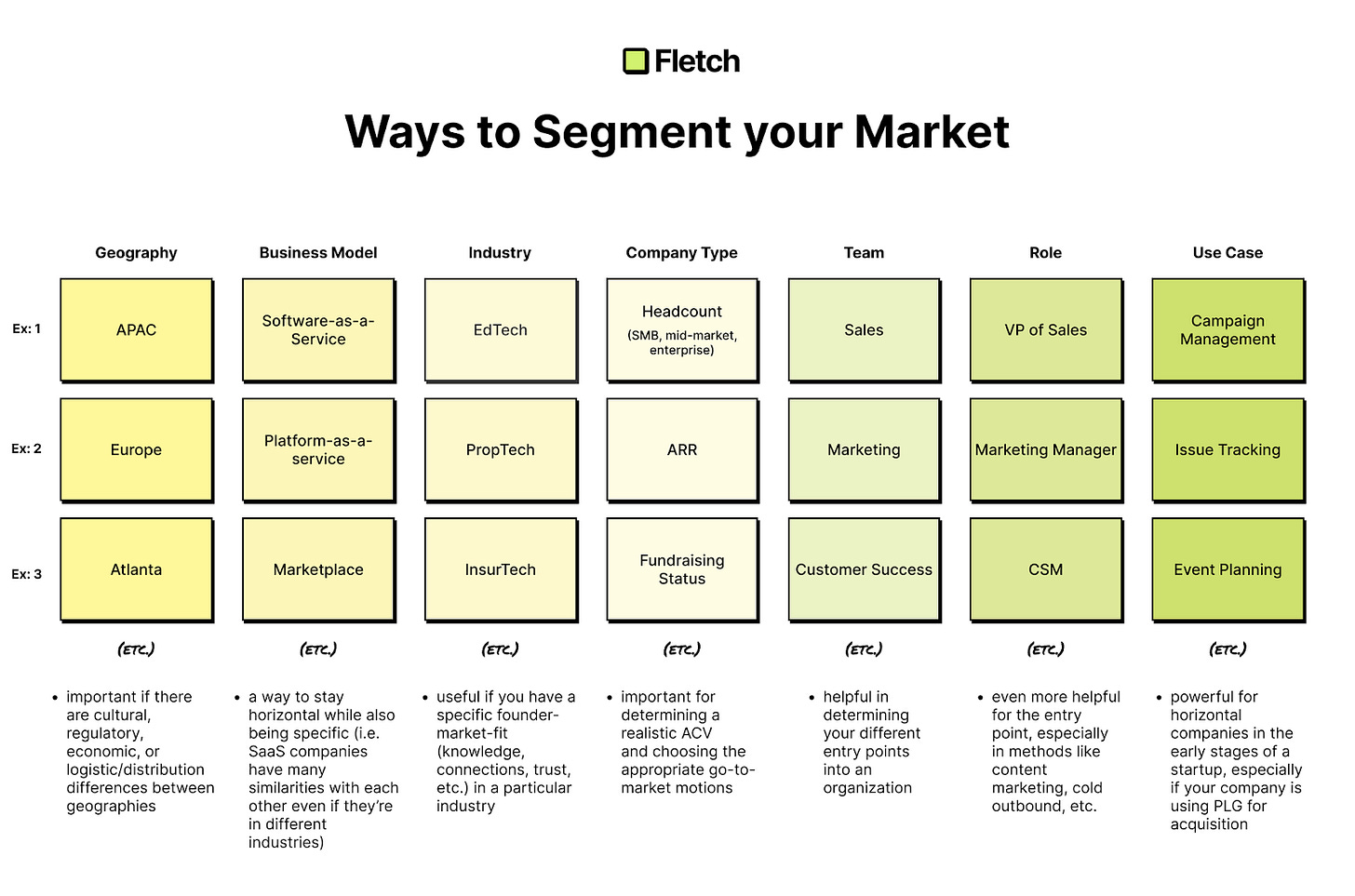

We need to divide the broader market into segments that our engineers could reasonably expect to please, our marketers could reasonably expect to reach, and our sales teams could reasonably expect to close.

Segmentation can quickly become a complicated exercise, as there are near infinite ways to slice up a market.

B2B markets are often segmented firmographically, using factors such as size (enterprise vs. SMB), industry (retail vs. logistics), or department (marketing vs. customer success).

B2C markets are sliced and diced more frequently by demographics (i.e. “this hair product is for males age 20-40 living in Chicago”) or psychographics (i.e. “our product is for people interested in organic foods, fitness, and wellness activities”).

Product categories can constitute market segments. One can speak of the market size for CRMs as the total of all people who want to buy CRMs in a given year (~$91B in 2023 and $101B in 2024).

Additionally, use cases can also form their own market segments. Jobs-to-be-Done theory defines a highly tightened use case (or “job”) as a segment all on its own.

Let’s look at the product SmallPDF. At launch, it allowed a user to upload a large PDF, then shrink it without losing fidelity. Their go-to-market strategy capitalized on SEO, reaching people who Googled “shrink a PDF.” The website gets roughly 45 million visits a month.

Does it matter if the people doing the Googling are in marketing, sales, or customer success? Does it matter whether or not they are in a large enterprise or an SMB? In the case of SmallPDF, the answer is no.

Zapier took a similar strategy. They created landing pages for all types of simple automations and integrations (i.e. “send an email whenever someone fills out a google form”). Each of these landing pages represented a different use case-based segment. When people searched for help for these specific tasks, they’d find Zapier.

Later, Zapier ran focused campaigns for specific department-based segments (i.e. “Here’s why Zapier is great for sales teams”). But initially? Their target segment was department and company-agnostic.

How should an early stage startup choose a segment? Unfortunately, it’s more art than science. It is more a reflection of the founder’s intuition, vision, and point-of-view than a quantitative or “data-driven” assessment. In fact, it’s an open secret among venture capitalists that business plans and market size projections in early stage pitch desks are essentially fiction.

As companies grow larger and get more customers, they can start to employ data in service of segmentation. However, this is far from a cookie-cutter, step-by-step mathematical process. Steve Jobs was faced with data that said customers didn’t want a phone without a keyboard… and he defied it to obvious success.

Despite the difficulty, companies must segment to be effective.

Once you’ve determined your segment, you can choose between category positioning or use case positioning. Select the approach that shows your product’s value most clearly and quickly.

Questions 3 & 4: What does it replace (and why is it better?)

Positioning is the art of choosing meaningful reference points to help explain the utility and value of your product in the quickest, clearest way possible.

As we’ve already discussed, both product category and use cases can be key reference points, reflected in a Use Case-Based Positioning strategy or a Product Category-Based Positioning strategy.

Another important reference point is the competitive alternative. What does your product augment or replace in the life of your customer? Your positioning strategy will help determine your competitive alternative and your differentiation.

Category-Based Positioning: Choosing a competitive alternative

(and finding your differentiation)

For Category-Based positioning strategies, there is only one type of competitive alternative: other vendors in your product category.

When The Browser Company explains the value of Arc Browser, they do so against the backdrop of other web browsers (like Chrome, Safari, and Firefox). Here is how they frame the competitive alternative on their website:

“This is a web browser. It’s just a frame, with some buttons and toolbars. It’s our window to everything on the internet. We love the internet, but it can be overwhelming. What if a browser could help us make sense of it all? Could a browser keep us focused, organized and in control? At the Browser Company, we're building a better way to use the internet.”

(You can read the entire manifesto here)

Similarly, Figma used the category “interface design tool” to explain their product. However, they called themselves “collaborative” — differentiating themselves from single-player options like Sketch and Adobe XD. Their homepage read: “The collaborative interface design tool: Finally you can do design work online, the way it should have been all along.”

This type of differentiation is key to a Category-Based approach. Choose a binary differentiation: something that you can claim but your competitors can’t.

DuckDuckGo is a great example. On their website, they state: "Unlike Chrome and other browsers, we don't track you.” For privacy-minded individuals, this difference is extremely powerful — and more importantly, it’s something Google would never say. Their business model depends on collecting data on their users.

Another example is Less Annoying CRM. Their dedication to small business is their differentiator. On their website, they say:

“Less Annoying CRM isn't a neglected spin-off of another big CRM, nor are we the ‘lite’ version of a more expensive system. Our goal 14 years ago was to build the best CRM for small businesses, and … we have no plans to change course.”

Positioning for small companies gives them a leg up on Salesforce and HubSpot, who focus on the enterprise.

Differences of degree are less compelling. (i.e. “We are easier to use.” “Our customer service is better.” etc.) While these claims may be true, your competitors can say the exact same thing—even if they’re lying. If this is your only viable angle, seek to find ways to validate your claims empirically. If you hold the top spot for “ease of use” on a review site or have a deep library of customer testimonials or case studies, you could make an effective case.

Use Case-Based Positioning: Choosing a competitive alternative

(and finding your differentiation)

With a Use Case-Based Positioning strategy, your main competitive alternative is the current way customers accomplish the use case (without your product).

For B2B software startups, this is usually a manual process or homegrown spreadsheet solution. You’ll want to emphasize how much improvement they’ll see with your solution. For example, User Evidence positions against manually collecting, organizing, and sharing customer quotes and testimonials.

Another example is Commsor, which was built for sales outreach (their use case). They position against cold emailing and cold calling, pointing out the declining effectiveness of these methods related to the use case. Commsor’s key differentiation is that they allow you to leverage your existing network to find warm leads, greatly increasing your chances of success.

Sometimes, the “current way” is another dedicated tool not in your product category. Here, show how using the wrong tool causes problems for them, and then highlight how your product was purpose built for the use case. For example, Zeda.io says: "Don't do product discovery in a planning tool” (“Product discovery” is the use case and “planning tool” is the competitive alternative.)

Remember: There’s no magic formula.

If you get this right, you won’t really know for at least 6 to 18 months. Positioning isn’t something you can A/B test — it’s a strategic decision that can really only be fully tested once your go-to-market motions have been adjusted to bring new prospects into the mix and then tracked through their entire life cycle.

With the new positioning…

Are they easier to reach?

Easier to close?

Faster to adopt?

More likely to renew?

More likely to share?

Just changing a homepage in isolation and comparing conversion rates will tell you almost nothing.

If you do want some immediate feedback, the best way to “test” positioning is to deliver it in a sales pitch to a real prospect, and then watch their reaction.

Again, this will only be an approximation. With the demand gen and brand building activities, a previously discounted positioning strategy can suddenly work.

Positioning isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach. Great positioning needs to be tailored to different audiences, reflecting the specific needs and knowledge of your market segments. Whether you choose a category-based or use case-based approach, the goal is to create immediate clarity and connection, enabling your product to stand out in a crowded marketplace.

Ultimately, the right positioning strategy aligns your product’s value with your target market’s expectations, setting the stage for deeper engagement, differentiation, and success.

Aatir again.

That’s a wrap! Hope you found this edition useful.

I’d like to thank Anthony for preparing these insights for us. Again, make sure to follow him on LinkedIn. Also, if your company is planning to redo its home page messaging, check out Fletch PMM.

Till next time,

Aatir

Wow, thank you for sharing these insights. Very interesting points that can be applied beyond positing SaaS!

Great insights. It enlightens me a lot, reviewing my old approach as a SaaS SDR, and improving my current approach as a SaaS CSM. Thanks. Aatir!